# GIT

Git works by recording the changes you make to a project, storing those changes, then allowing you to reference them as needed.

# Git Basic Commands

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

git init | Create repository (=Folder with superpower) |

git status | Show Status |

git add <Filename> | Add File |

git add . | Add all Files |

git diff | check differences between the working directory and the staging area |

git commit | stores changes (opens vim - close with :x ) |

git commit -m "message" | commit with message |

git log | show log |

git --help | get help |

# git init

Create repository (=Folder with superpower)

Git project can be thought of as having three parts:

- A Working Directory: where you’ll be doing all the work: creating, editing, deleting and organizing files

- A Staging Area: where you’ll list changes you make to the working directory

- A Repository: where Git permanently stores those changes as different versions of the project

In Git, we save changes with a commit,

# git status

Show Status

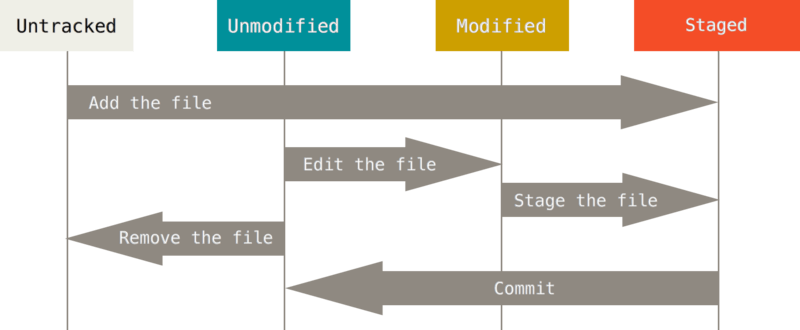

git knows 4 States of files:

- Untracked - If you create a new file locally, it is firstuntracked. Git knows that it is there, but it won’t do anything with it.

- Unmodified - All changes that you committed now have the status unmodified.

- Modified - If you now change a file that has been added or committed before it is modified

- Staged - If you add a file with the git add command, the file gets staged. git knows the file, has collected all changes and willinclude them in the next commit

# git add

Before doing a commit, you have to collect all your changes -> stage them.

git add <Filename> - Add File

git add .- Add everything

git add *.txt - Add all txt-Files

git add <filename_1> <filename_2> - add multiple files at once

# git diff

check the differences between the working directory and the staging area with:

git diff *filename*

- Changes to the file are marked with a

+and are indicated in green.

# git commit

A commit is the last step in our Git workflow. A commit permanently stores changes from the staging area inside the repository.

git commit -m "Complete first line of dialogue"

Standard Conventions for Commit Messages:

- Must be in quotation marks

- Written in the present tense

- Should be brief (50 characters or less) when using -m

git commit - will open vim. Write the commit message and close with :x

# git log

Commits are stored chronologically in the repository and can be viewed with:

- A 40-character code, called a SHA, that uniquely identifies the commit. This appears in orange text.

- The commit author (you!)

- The date and time of the commit

- The commit message

If the log is getting too long, git will show a colon :at the end. This means: you are in scroll mode. You can scroll down or up with your arrow keys. Exit the scroll mode by typing q

$ git log --pretty=onelinegit lg

# git reset --soft HEAD~1

Undo last commit by resetting it.

- The

--softflag has the effect that all changes of your last commit are not deleted, but they are now uncommitted modified files. - The tilde ~ sign followed by a 1 means: take the HEAD (your current position in the git history) and reset one commit from there

# Undoing Changes

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

git checkout -- . | discard all changes in all modified files |

git checkout -- <file> | reset file |

git reset --soft HEAD~1 | undo the last commit by resetting it |

git reset --hard HEAD~1 | delete all changes of the last commit permanently |

git reset HEAD . | remove all files from the stage |

git reset HEAD |

# git checkout --

git checkout -- . - discard all changes in all modified files (The dot is a shortcut for all files)

git checkout -- <file> - Resetting Modified Files: undo local changes,

# git reset

git reset HEAD - Removing files from the stage - If you have staged files, but you don’t want to commit them

git reset HEAD . - remove all files from the stage

git reset --soft HEAD~1 - undo the last commit by resetting it.

- The --soft flag has the effect that all changes of your last commit are not deleted, but they are now uncommitted modified files.

- The tilde ~ sign followed by a 1 means: take the HEAD (your current position in the githistory) and reset one commit from there

git reset --hard HEAD~1 - delete all changes of the last commit and never see them again.

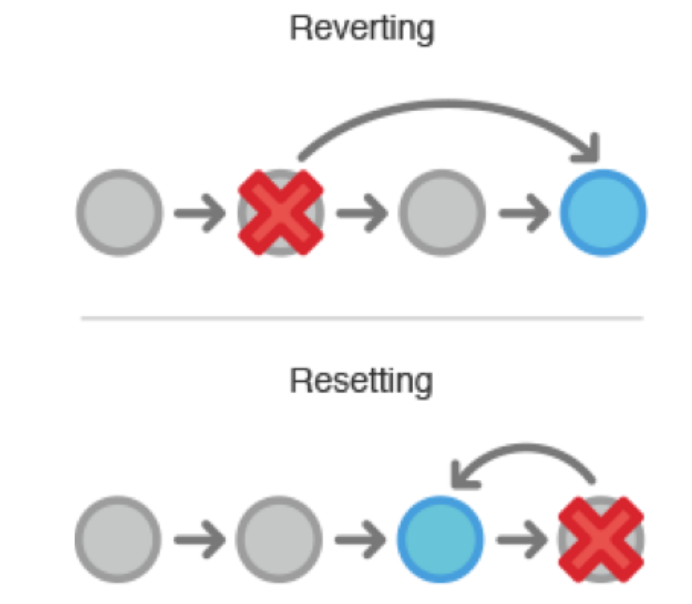

# Revert vs Reset

The difference is: if you reset a commit, you remove it; if you revert a commit, you add an additional commit to the history that undoes the changes.

Use Reset when: You want to undo the lastcommit(s).

Use Revert when: You want to undo a commit that is some commits back in the commithistory and it is important that you see in the point in the commit history when the revert has been done (may be important in large projects with many developers).

# Backtracking

# head commit

The commit you are currently on is known as the HEAD commit. In many cases, the most recently made commit is the HEAD commit.

# See the HEAD commit

git show HEAD

# Discards changes

git checkout HEAD filename

or shorthand: git checkout -- filename

Discards changes in the working directory. To restore the file in your working directory to look exactly as it did when you last made a commit

# Unstage a file from the staging area before it is commited

git reset HEAD filename

Unstages file changes in the staging area. -> resets the file in the staging area to be the same as the HEAD commit.

Notice in the output, “Unstaged changes after reset”:M scene-2.txt M is short for “modification”

# Resets to a previous commit

Git enables you to rewind to the part before you made the wrong turn. You can do this with:

git reset *commit_SHA*

Resets to a previous commit in your commit history. This command works by using the first 7 characters of the SHA of a previous commit. For example, if the SHA of the previous commit is 5d692065cf51a2f50ea8e7b19b5a7ae512f633ba, use:

git reset 5d69206

-> and then git chekout *filename*

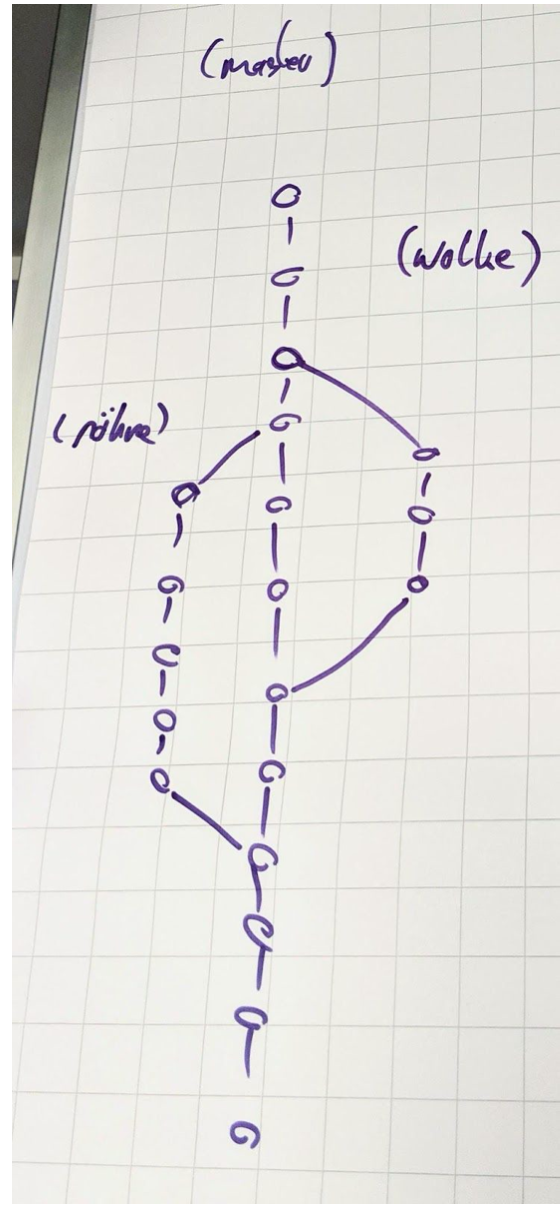

# GIT Branches

A branch is a string of commits that is independent of the other commits.

- The master branch is usually the default branch.

- If you want to make changes independently from the other developers, you create a branch. When you are done, these can be merged back to the master branch.

Keep in mind:

- Your goal is to update master with changes you made to fencing.

- fencing is the giver branch, since it provides the changes.

- master is the receiver branch, since it accepts those changes.

# Commands

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

git branch | Shows all existing branches, marks the one you are on. |

git branch <newbranch> | Creates a new branch |

git checkout -b <newbranch> | Shorthand: Create new branch and switch |

git branch -d <oldbranch> | Delete branch |

git branch -D <oldbranch> | Delete unmerged branch |

git merge <name> | Merge branch into the active branch |

Branch names can’t contain whitespaces

# Workflow: Merging a branch into master

- you need to be on the master branch -

git checkout master - Then, merge your branch into master -

git merge branchname - You don’t need the merged branch anymore, so you can delete it. -

git branch -d branchname

# Best Practice:

- Always delete branches that you don’t need anymore. The less branches you have, the better: it is much less confusing.

- Make it a habit to delete old branches before you create a new one.

An example for a popular branching strategy for larger teams with continuous delivery: A successful Git branching model (opens new window)

# Merge conflict

git merge branchname

We must fix the merge conflict.

<<<<<<< HEAD

master version of line

=======

fencing version of line

\>>>>>>> fencing

Git asks us which version of the file to keep

Delete all of Git’s special markings including the words HEAD and fencing. If any of Git’s markings remain, for example, >>>>>>> and =======, the conflict remains.

In Git, branches are usually a means to an end. You create them to work on a new project feature, but the end goal is to merge that feature into the master branch. After the branch has been integrated into master, it has served its purpose and can be deleted.

# Git stash

GitHub →